KARACHI:

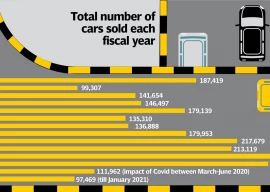

Last week when auto sales data was released, everyone jumped with joy. Why shouldn’t they? Sales figures for March 2021 increased 27% month-on-month, and since year-on-year comparison really isn’t fair due to the lockdown in 2020, everyone saw this as a delightful development for a sector that has various industries associated with its recovery.

Figures for the nine-month period – between July 2020 and March 2021 – were even better with sales amounting to near 135,000, a 36% increase year-on-year. Now this figure is worth celebrating even more because, in the strictest sense, it takes away the months of inactivity due to the pandemic, and gives a closer picture of how much the auto sector has recovered. It compares the nine months during the time when interest rates were higher, economic activity was lower, and inflation was keeping citizens on their toes.

It seems as if this sector, touted as a backbone for Pakistan’s economy and that carries one of the highest weightages in the country’s large-scale manufacturing sector after textiles, food & beverages, and a few others, is seen as a benchmark for the country’s path to recovery.

Read: Auto production plunges to lowest since 2010

However, much of this celebration around higher sales figures is owed to two to three factors alone. A lower interest rate has enabled Pakistani buyers to turn towards consumer finance as they work their way towards making monthly rentals. The outstanding position of consumer financing under the category of “for transport” has gone beyond Rs272 billion with an additional Rs30 billion coming from bank employees who have also availed the cheaper loans. This loan category under ‘personal borrowing’ has registered the single-largest percentage increase between June 2020 and February 2021, and suggests the close relation between auto sales figures and interest rate levels.

Granted that there are other reasons why auto sales have picked up – when I wrote a few weeks ago that the country’s auto policy has paid some dividend – cheaper finance should probably qualify as the biggest determinant. An addition of Rs61 billion in loans outright meant for transport during eight months is no mean feat. Additionally, the share of financing in total car sales has reached 40-50% by February 2021, according to a note by a brokerage house, a massive jump from its share of 20-25% in March 2020.

Having recognised that much of the increase in auto sales figures has come on the back of cheaper financing, one now starts to wonder what would be the effects of this pickup in activity.

The answer lies in the large-scale manufacturing growth figures that convey automobiles alone contributed 0.7% year-on-year growth impact in the overall 7.4% increase registered during July-February of the ongoing fiscal year.

While substantial and worth giving credit for, all this growth has come at a cost – like it always does for every country. This is the elephant in the room – the import bill, and brings us to Pakistan’s biggest curse. Its growth comes at a massive cost, and takes away the shine off robust economic activity in the country.

During the nine months of the ongoing fiscal year, imports under the transport group have registered a 69% increase, from $1.2 billion to $2.02 billion. This $800 million increase in Pakistan’s import bill during nine months has a lot to do with increased auto sales, and the parts auto industry needs to assemble vehicle units.

In no way am I advocating reducing imports. What I am pointing out, however, is that imports under the transport group registered the largest increase in dollar amount, which was bigger than the ones registered by the food (54%) and textile (45%) groups. To put things in context, overall imports during the nine-month period increased 14%.

This entire clutter of numbers, and arguments, is to make this point – the auto sector is responsible for a huge proportion of imports, and adds very little value to the equipment it brings in. A low interest rate, key for Pakistan’s economic growth, adds massively to auto sales figures, but adds to the country’s trade deficit as well.

Another argument, and this is key, is that Pakistan’s car prices have increased substantially since 2017 when the dollar rate started to slip out of control. This is largely because a huge component of a vehicle, assembled in Pakistan, is manufactured elsewhere. If one now buys their argument – that dollar rate is a big component of their cost – then it is also true that they are responsible for importing a huge proportion of their vehicle. And this is where the failure lies – of the auto companies, and the policymakers.

Read more: Auto industry demands duty removal

Auto companies are quick to point at rupee depreciation for an increase in the price of their product, but also have to take a share of the blame when experts say Pakistan’s economic growth is dependent on imports.

Now I am not arguing that Pakistani companies should manufacture more equipment in the country – that would be too simplistic an argument – but if their stance is that in more than two decades, they haven’t figured out a way to increase their sales/profits without relying on government policies that place duties on car imports, and a low interest-rate environment, then something is quite wrong.

The cycle, as it so seems at the moment, is that the government place massive duties to discourage citizens from buying ‘made elsewhere’. Low interest rates would increase sales, even as car prices shoot to levels that go beyond rupee depreciation, and car loans would cover the delta and give consumers artificial buying power. Banks win, auto companies win, and consumers are left scrambling to pay monthly amounts for years.

Meanwhile, value-addition on imports associated with the auto sector would remain negligible, and ‘localisation levels’ remain restricted to number of parts in a vehicle, and not cost. How else would you explain up to a 60% increase in the prices of some cars, proportionate to the rupee-dollar change. This tells us the ‘localisation level’ Pakistan’s auto sector has achieved in over two decades.

The writer is former business editor of The Express Tribune, and winner of the Citi Journalistic Excellence Award 2018. He holds a MBA from Cass Business School, and is currently associated with the CEJ-IBA. His Twitter handle is @bilala_memon

Published in The Express Tribune, April 19th, 2021.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ